METAPHYSICS OF THE PHOTOGRAPH

by Geoffrey Klempner

'I don't take pictures; pictures take me.' — Charles Harbutt

'I photograph to see what things look like photographed.' — Gary Winogrand

Photographs occupy a peculiar place in the human world, half way between the things we find and the things we make. They are ours and yet not ours, precious flakes of reality that have worked themselves loose which we gather up and store away.

You can make art out of anything; but a photograph has an innate recalcitrance which resists being taken over and claimed as a 'work'. That's why I am uncomfortable with the idea of an aesthetics of photography. So don't ask me, 'Is photography art.' A camera is a tool, like a chisel or a paintbrush. In the hands of an artist, it can no doubt contribute to the production of artworks, although for reasons just stated it seems an odd, rather clumsy tool for that purpose.

My quarry is the photographer who takes photographs for photography's sake; not the would be photographer-artist. Given that our concern is not with aesthetics, the only remaining justification for such an endeavour is philosophical. In the hands of the true photographer, the camera is a device for gaining a priori insight into the nature of reality. A portfolio of photographs can serve the same, or similar, purpose as a metaphysic.

It goes without saying that I will not be talking about the practical uses of photography — family snapshots, photojournalism, advertising photography, police photography, medical photography, astronomical photography etc. The practical interests of the photographer range far and wide — literally, from the tiniest particles known to science to the edges of the universe. But they are all mundane. The metaphysician eschews anything mundane.

There doesn't seem to be a lot left, if you give up any interest in the aesthetics or practical uses of photography. But actually there is something else that should be excluded, although this gets closer to the bone, and maybe, ultimately, I can't altogether exclude it. I'm thinking of photography as a pathological phenomenon: tourists who would sooner photograph a scene rather than open their eyes and ears and experience it, the fetishism of ever more luxurious and expensive camera equipment, paparazzi pursuing celebrities to nervous breakdown, ubiquitous cctv and webcams, the vast industry dedicated to internet erotica.

It's close to the bone because there is something — I believe — pathological about metaphysics too (which Richard Rorty analyses brilliantly in his book Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature). Or, rather, something which as a metaphysician one must remain perpetually on guard against. If photography, as I am arguing, is a way of doing metaphysics — or at least if photography has something essential in common with metaphysics — then it follows that you can do good metaphysics with a camera, or bad.

I'm not going to say too much about the question of how, or in what sense metaphysics might be considered pathological. It has to do with the questionable model of the self as a passive observer, which philosophers up until the beginning of the 20th century had taken on trust, ever since Descartes enunciated his 'Cogito ergo sum'. The photographer who forgets that we are agents in the world and becomes instead a voracious, disembodied eye is indeed a pathological specimen, has gone over to the dark side.

But I'm digressing.

The main thing I wanted to say is upbeat and positive: the camera, to me, is one of the most incredible, wondrous things ever invented.

It is scary and thrilling what a single photograph can do; what it can reveal, and also what it does to us, the effect that it has on the viewer. The border of the photograph is like a magic portal through which things themselves appear; a phenomenon so common, yet so often misinterpreted and misunderstood. Like sorcerer's apprentices we carelessly flash our digicams unaware of the true significance of our actions.

My interest in photography predates any interest in academic philosophy. A twenty year old university dropout, I dreamed of being a photojournalist or advertising photographer. I jostled with press photographers outside Magistrates courts, held a light meter up against a naked model's chest to get the exact f-number of her skin tone (the advertisement, as I recall, was for fertilizer), tramped the streets of London looking for that ever-elusive 'decisive moment'. But then I opened a book of philosophy and was hooked. After that, most of the pictures I took were in my head.

(But not all. I still use the Pentax Spotmatic camera I purchased with half my first-year Leeds University grant money back in 1969.)

When I was very young, long before I owned a camera, like kids do I used to love looking through coloured sweet wrappers and seeing the world all pink, or blue, or green. I would lie on my back at the top of the stairs with my legs stretching up against the wall, imagining that the ceiling was the floor and wondering what it would be like to live in a world where everything was upside down. I placed two facing mirrors in a shoe box, and squinted through a small hole scraped in the silver back of one of the mirrors at the darkening tunnel of reflections extending to infinity.

Mirrors have a special significance for the photographer. Lewis Carroll's Alice Through the Looking Glass captures brilliantly the sense of mystery of the looking glass world that we can touch but never enter except in our dreams. If you are above a certain age, you will remember the fun and magic of the fairground hall of mirrors. That was before video games.

My thesis is that the photograph is like the distorting mirror, or the coloured sweet wrapper. Like the distorting mirror or sweet wrapper, it releases us from a certain narrow or conventional way of seeing the world. It creates and also does not create the reality which exists within the borders of the image or print. What matters crucially, however, is the way it does this. To quote from the title of the current BBC TV series on photography, that is the secret 'genius' of photography.

Before I pursue that line of thought any further, I want to come at the issue of photography from another angle. The way I've been talking, you might think that all one has to do is point a camera in any direction and click the shutter. What does it matter what you photograph, or how?

And yet it matters immensely. The agonizing thing, which any photographer (or 'creative photographer', I don't much like that word but that is what we are talking about) will tell you is how hard it is to take a significant picture. In that particular mood, fleeing from the mundane, you look around a room — or up and down a street — and all you see is a chaotic world of jumble and rubble. From all sides one is assailed by the accidental, the pointless brute existence of things. Sartre's description of the tree root in La Nausee captures the feeling perfectly.

There are various reactions to this existential predicament which define the project that one is engaged in, as a creative photographer. I said I wasn't interested in aesthetics. However, it will be necessary to consider the attempt at an aesthetic response in order to see why making beautiful pictures fails to reckon with the pointlessness of things.

There's plenty of beauty in nature to capture in a photograph if that's what you're after. Nelson Goodman in Languages of Art quips that 'there's nothing like a camera to make a molehill out of a mountain,' yet the resourceful photographer succeeds impressively in avoiding the downsizing effect of the camera lens. Take, for example, Ansel Adams' masterly black and white prints of Yosemite National Park. The problem for me, however, is that the beauty was already there. For all his artistry and technical skill, Adams is just visually reporting on it.

Or you can attach a close-up lens and seek to capture 'the thing itself' in all its glory as Edward Weston did. There is no denying the power of Weston's photographs, the glistening dark peppers that look like nudes, the cream and white shells that look like vulvas, the nudes that look like — rock formations. Inspired by a Walt Whitmanesque sense of the universal rhythm running through all creation, you could almost say that Weston's photographs border on the metaphysical. The problem is that like his disciple Adams, Weston is ultimately hooked on beauty and visual appeal.

Or going in completely the opposite direction you can make creative compositions from any random subject matter by careful choice of lens and viewing angle. However, for all one's efforts the result is just a pretty arrangement of the pointless and accidental. A row of grimy cigarette ends photographed by Irving Penn and printed large on platinum paper is still a row of cigarette ends. A photograph of a tangled tree root is just another thing to gaze at and feel horrified by.

Or you can take refuge in the belief that human beings are ultimately the only subjects worth photographing. The 'Family of Man'. I think you already know what I'm going to say about that conceited notion. Today, we are assaulted on every side by photographs of people. They leer at us from newsstands and advertising hoardings. We have become obsessed by the visual appearance of the body and the face. Portrait and figure photography is picture taking at its most pathological.

The inescapable fact is that the world is a human world. The human being is in every photograph you take, whether you actually see a human being there or not, just because the photograph was taken by a human being. But that is not news. The common factor, factors out.

So what is left?

I could start very simply by explaining why, these days, I don't get much pleasure from looking at things through coloured sweet wrappers. Jumble and rubble coloured pink or blue or green is still jumble and rubble. As a device for shaking our perceptions free from conventional ways of seeing, coloured cellophane is not very effective.

(It should hardly need stating that the same goes for fisheye and distorting lenses, filters that create spangly star effects, and all the other absurd contraptions from the amateur photographer's gadget bag.)

At the most abstract level, one can say that the photographer's task is not to compose, but rather to juxtapose. Composition is a pictorial concept, whose varieties and rules are studied by aesthetics. Juxtaposition has no rules. Or, if you want to be pedantic, the only rule is that it takes the unique event of clicking the shutter at that particular moment to make the juxtaposition apparent, to make it exist.

The things that impress us as we cast our eyes around belong by definition to conventional ways of seeing. We see, we notice, what in a sense we were already looking for: the doll on a rubbish tip, the reflection of the moon on a lake, the owner who looks like her dog, a red kite against a blue sky, the sad face in the happy crowd. In short, the bread and butter of amateur photo clubs.

Photographic juxtaposition has no rules, no syntax or semantics. It is not a language. Or, equally, each original photograph is like a new language created from scratch that the viewer is required to learn in order to appreciate what that particular photograph says and shows.

It is truistic that one tries to avoid visual cliches. I'm saying more than this. I am talking about a kind of photography whose primary purpose is to challenge our conventional ways of seeing. It follows that there cannot be such a thing as an 'easy' photograph, one whose point one grasps right away. A photograph is a mandala to meditate upon, a puzzle to solve (it might have multiple 'solutions'), an uncracked fragment of code.

You can draw a puzzle drawing or paint a puzzle painting, but you can only put onto the paper or canvas what was already in your mind, in your thoughts and feelings. The secret of photography is its recognition that the human mind is finite but reality is infinite. To engage in creative photography is to be involved in a pre-eminently mind-expanding activity.

It is hardly surprising that great photographs are hard to come by. The accidental and uncontrollable nature of lived reality is an unending source of original material. Yet — as I discovered long ago — for every gold nugget, there are tons of rubble to sift through and discard.

Photographs are discovered. The creativity comes in because, in the words of Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, 'The real cycle you're working on is a cycle called yourself.' Like the hunter of some elusive quarry, you are constantly refining your sensitivity, your speed, your skill.

Now I come to the important part.

The idea of infinity which I mentioned a moment ago is the first clue to what photography might have in common with metaphysics.

(Those of you are still with me, might begin to waver at this point. I accept that what I am now going to say is controversial — if indeed it makes any sense at all to say it.)

'Metaphysics,' F.H. Bradley said (in the Preface to his monumental Appearance and Reality) 'is the finding of bad reasons for what we believe upon instinct. But to find these reasons is no less an instinct.'

What Bradley had in mind was something like this. You have an instinctive feeling, e.g., that despite the multiplicity of appearances, reality is One. (Remember Weston.) The metaphysical philosopher then goes and proves it, by demonstrating that the very notion of a 'relation' between two entities is self-contradictory. Hence, there can be no such thing as 'space', no such thing as 'time', indeed no such thing as a 'thing'.

I agree with Bradley that in a sense, Metaphysics comes before the finding of reasons, good or bad. The belief that 'everything is One' is a metaphysical vision. Another example of a metaphysical vision is Bishop Berkeley's theory that when you look out onto the world, you are really looking at the inside of God's mind. Or Leibniz's theory that we are, each of us 'windowless monads' alone in our own private reality, each dreaming the same dream called 'the world'. I haven't given Berkeley's or Leibniz's arguments. The point, however, is that you can convey a vision without the aid of logical argument. Logic always comes after.

I could describe the metaphysical visions of Parmenides, Plato, Spinoza, Kant, Schopenhauer, Hegel. But I wouldn't want to take away the fun of finding out for yourselves.

I believe that there is some truth in every metaphysical system, which makes me the worst kind of 'eclectic'. Bradley has something to say about this. According to the eclectic, 'Every truth is so true that any truth must be false.' I agree. A vision by definition cannot be false. If you see it, then it must be true. A vision cannot be denied. But since metaphysical visions patently contradict one another, one either has to believe the truth of a contradiction or concede that nothing can be 'true'. I agree with that too.

What is true, is the all-pervasive lie that the very existence of metaphysics — or creative photography — exposes. Earlier, I referred to it blandly as our 'conventional ways of seeing'. We take the world for granted. It is so familiar to us, in fact, that one has great difficulty in grasping that we see the world as anything at all. The world is just the world, what's so special about that?

The idea that relations are self-contradictory, or that the tree outside the window only exists in God's mind, or that we are all solitary monads, shatters this easy going commonsense view. Metaphysics poses the questions that one never thought to ask.

As does creative photography.

The same point can be put more simply and much more devastatingly: there is no world. All seeing is 'seeing as'.

A single photograph does not a treatise make. Nor is a portfolio of photographs equivalent to a finely crafted metaphysic. Yet each original image chips away at the foundations of your 'world' — while you hardly notice the ground crumbling beneath you.

Slides

After the talk, I showed photographs by Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Charles Harbutt, three photographers whose work had a strong influence on me in the early days. I also showed photographs which I have taken. The photo series Chesterfield Road was done especially for the talk.

Web pages

Camera Dreamer http://cameradreamer.net

Camera Dreamer Blog http://cameradreamer.blogspot.com

G.Klempner on Flickr http://flickr.com/gklempner

© Geoffrey Klempner 2007

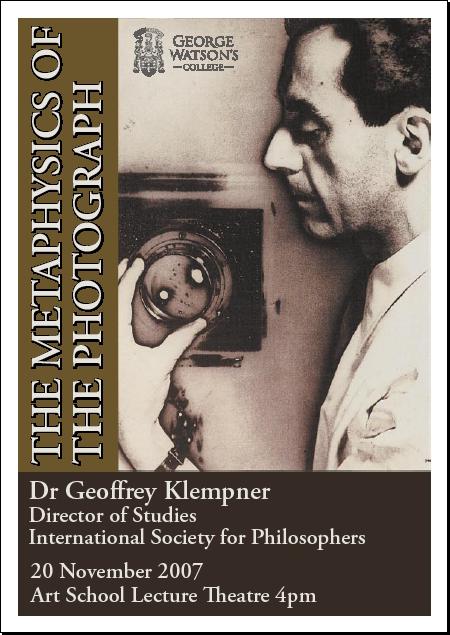

Presentation given to staff and students at George Watson's College Edinburgh on 20 November 2007. The poster was designed by Andrew Watson, who teaches in the Art department at George Watson's College. The photograph in the poster is a self-portrait by Man Ray. I took the photos of the audence with a Vivitar T201 fixed lens 35mm flash camera.