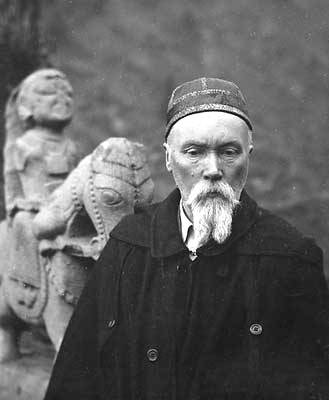

Nikolay ROERICH (RERIKH) (9.10.1874, St. Petersburg, Russia — 13.12.1947, Naggar, India) — Russian philosopher, painter, archaeologist and mystic.

Son of a well-off notary public, Roerich attended the Imperial Academy of Arts (1893-1897) and, simultaneously, studied law at St. Petersburg University. Early in his career, Roerich distinguished himself as his generation's greatest painter of scenes from ancient Russian history; representative works include The Messenger (1897), Visitors from Overseas (2 versions, 1901 and 1902), Slavs on the Dnieper (1905), and Battle in the Heavens (2 versions, 1909 and 1912). Roerich was associated with several Symbolist literary-artistic journals, including The Golden Fleece, as well as the World of Art Society, which he chaired from 1910 to 1916. From 1906 to 1917, he directed the School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. Like many of his World of Art colleagues, Roerich designed productions for Diaghilev's famed Ballets Russes; he is best known for his work on 'Prince Igor' (1909) and 'The Rite of Spring' (1913), the libretto of which he co-wrote with Igor Stravinsky.

After the October Revolution, Roerich and his family left Russia. As emigres, they lived in Finland, England, and the United States, finally settling in northern India. Roerich remained a prolific painter, but other activities now overshadowed his artistic career. He spearheaded an international campaign for the adoption of a treaty — the 'Banner of Peace' Pact — to protect art and architecture in times of war (signed by the United States and over twenty Latin American countries in 1935; incorporated into UNESCO conventions after World War II). In 1921, Roerich and his wife Elena, already confirmed Theosophists, founded their own occult tradition: Agni Yoga, the 'system of living ethics.' Most famously, Roerich led two expeditions (1925-1928 and 1934-1935) to the Himalayas, Tibet, Mongolia, Central Asia, and Manchuria. The ostensible purpose of these expeditions was to allow Roerich to paint scenes of Asia, as well as to conduct research into these regions' archaeology, folklore, and natural history. In reality, the Roerichs, driven by their millenarian belief that a utopian 'new era' was at hand, aspired to create nothing less than a pan-Buddhist kingdom in Asia. The precise nature of the Roerichs' actions remains a matter of intense debate and has led to accusations of espionage, political adventurism, and fraud. Because one of Roerich's closest followers was, for a time, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture (later Vice-President) Henry Wallace, Roerich's activities briefly affected the political fortunes of Franklin Roosevelt's presidential administration.

Roerich's expeditions led to the publication of several well-known books, including 'Altai-Himalaya' (1929) and 'Heart of Asia' (1929), but he failed in his political goals. He spent the last decade of his life in quiet semi-retirement in India, where he befriended such luminaries as Nobel prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore and politician Jawaharlal Nehru.

Roerich enjoyed a reputation as one of the Silver Age's most intellectually versatile painters. He was respected as a historian and as a gifted amateur in the field of archaeology. As a student and during his early career, he was influenced by the Arts-and-Crafts ideals of John Ruskin and William Morris; these ideals were reinforced by his friendship with educator and patroness Princess Maria Tenisheva. Roerich maintained a lifelong interest in the teaching of art, as well as the preservation of artistic and architectural heritage, as demonstrated in essays such as 'The Golgotha of Art' (1908) and 'Quiet Pogroms' (1911). Like many others in the Diaghilev set, Roerich was an ardent admirer of Wagner, subscribing wholeheartedly to the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or 'total art work.'

Even more central to Roerich's worldview was the question of Russia's cultural and historical connections to other civilizations, especially those of Asia. Major writings on this subject include 'On the Path from the Varangians to the Greeks' (1900) and 'Joy in Art' (1908). Inspired by his archaeological research and his early friendship with famed critic Vladimir Stasov, Roerich followed a line of thinking similar to those associated with the later 'Scythian' and 'Eurasian' movements. Roerich never belonged formally to either group, but he was acquainted with many who did — such as poets Aleksandr Blok and Nikolai Gumilev, as well as the art historian Nikolai Kondakov — and he agreed with them that Russia was best understood in a fully Eurasian context.

No discussion of Roerich's thought can be complete without mention of his mysticism. As a young man, Roerich, like many members of the Silver Age's intellectual elite, subscribed to the idealist supernaturalism of poet and philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, according to whom art could exert a meaningful transformative power on the world. He was also prone to the 'pan-cosmic' thinking common to Russia's Symbolists and later denounced by philosopher Nikolai Berdiaev. After about 1905, Roerich and his wife became increasingly attracted to Eastern religions, especially Buddhism, and esoteric doctrines such as Blavatskian Theosophy. Over time, the Roerichs became among the most literal-minded and millenarian of the many Russian artists and thinkers drawn to the occult during the fin de siecle. Roerich's thinking became noted for a distinct unity of vision: in essays such as 'Art and Archaeology' (1898), he argued that scientific thought, artistic creativity, and spiritual advancement were equally important and mutually interdependent. Before and during the revolutions of 1917, Roerich came to advocate a past-oriented form of communalism, an idea given its fullest expression in The Rite of Spring; Roerich believed that Russia could avoid the dehumanizing forces of the modern era by returning to what he saw as the pure spiritual values of the pagan Stone Age.

Roerich's imprint on Russian culture and thought continues to be felt. His art enjoys considerable popularity. Agni Yoga endures today; major (but competing) centers of the movement operate in the United States, Russia, and elsewhere. Roerich's art and ideas are also powerful symbols for those who propose various neo-Eurasianist conceptions of Russia and its place in the present-day world. In Moscow, the Museum of the East and the Roerich Museum house large collections of his art; the latter is home to the International Center of the Roerichs, which continues his cultural and spiritual work. The Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York is the largest center of Roerich-related activity outside of Russia.

-=-

by Roerich

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. Sobranie sochinenii. Moscow: Sytin, 1914

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. Altai-Himalaya. New York: F. A. Stokes, 1929

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. Iz literaturnogo naslediia. Moscow: Izobrazitel'noe iskusstvo, 1974

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. Heart of Asia. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 1990

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. Listy dnevnika. 3 volumes. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnyi tsentr Rerikhov, 1999-2002

Rerikh [Roerich], N. K. and Helena Roerich. Agni Yoga. 13 volumes. Moscow: Eksmo, 2002 [English edition, New York: Agni Yoga Society, 1952-1962]

on Roerich

Archer, Kenneth. Nicholas Roerich: East and West. Bournemouth, U.K.: Parkstone, 1999.

Belikov, P. F., and V. P. Kniazeva. N. K. Rerikh. Samara: Agni, 1996.

Decter, Jacqueline. Messenger of Beauty: The Life and Visionary Art of Nicholas Roerich. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street Press, 1997.

McCannon, John. 'Searching for Shambhala: The Mystical Art and Epic Journeys of Nikolai Roerich.' Russian Life 44, no. 1 (January-February 2001): 48-56.

Poliakova, E. I. Nikolai Rerikh. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1983.

Rosov, V. A. Nikolai Rerikh: Vestnik Zvenigoroda. 2 volumes. Moscow: Ariavarta, 2002-2004.

-=-

© John McCannon, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof.

University of Saskatchewan (Canada)

E-mail: mccannon@skyway.usask.ca